Artikel zuerst veröffentlicht von dm aegean und V.H.

The following short report is based on data collected by the organization Christian Peacemaker Teams Lesvos (CPT-Lesvos) who has been monitoring smuggling trials since 2014. All graphs have been made by CPT-Lesvos. An in-depth analysis of the data collected will be published in autumn 2019.

Criminalizing Migration and Escape Aid

Many people who reach the Greek islands in rubber dinghies have been travelling for months or years to find freedom and safety in the European Union. But surviving the crossing of the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece does not mean that they eventually reached safety.

On the Greek hotspot islands, some migrants are regularly arrested from their boats and directly detained and accused of human smuggling. The European Union claims:

“Fighting and preventing human smuggling and trafficking is one of the priorities of the European Union and crucial to address irregular migration in a comprehensive way.”

European Union, 15.10.2018[1]

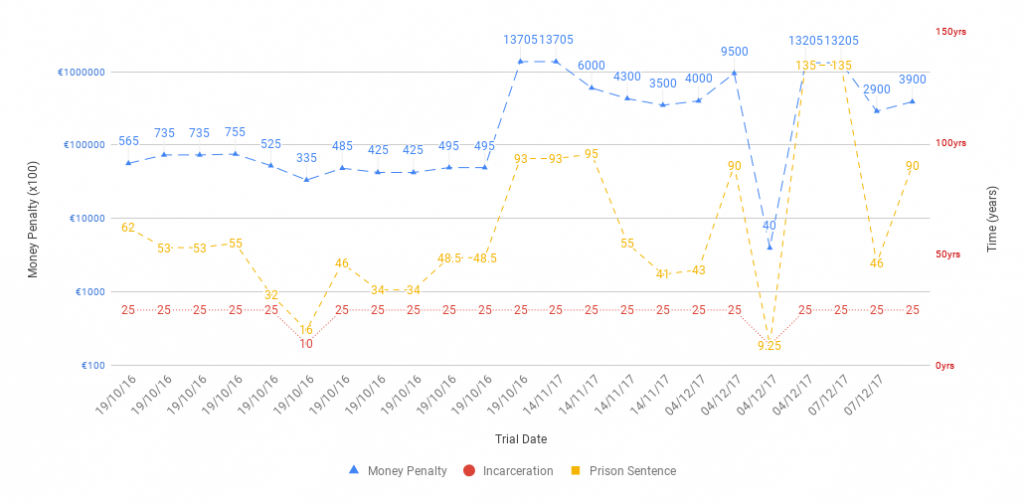

Jamil from Afghanistan (name changed) experienced what this means. He was sentenced to 90 years in prison of which he will have to serve 25 years and was also convicted to a 13,000 Euro penalty. Jamil was captured driving a refugee boat from Greece to Lesvos. He could not afford to pay for his wife’s and his own journey, so he accepted the offer from the smuggler who asked him to drive the boat and return to get a free ride with his wife. He did not know that driving a boat would be considered a crime. While his wife now lives in Germany, he is still imprisoned – he appealed the court decision but was again convicted.

His example shows that the maxim of fighting human smuggling is not only used to criminalize civilian sea rescue as in the cases of the recent accusations against the captain of the Sea Watch 3 and the crew of the rescue boat Iuventa. It however impacts people who do not hold European passports much more directly. Many of them come as refugees themselves, intending to seek asylum in Europe. While European sea rescuers have so far only been accused for crimes but not convicted, hundreds of migrants have been sentenced to decades in prison with excessive charges.

Arresting “smugglers”

The organization Christian Peacemaker Teams Lesvos (CPT-Lesvos) has been monitoring the smuggling trials since 2014. They found that most of the people accused of smuggling are Turkish citizens and some of them migrants from other countries seeking protection in Europe. All people arrested are male. CPT-Lesvos member Rûnbîr Serkepkanî explains:

“What is common among most of them is that they are poor, they are students, they are migrants who couldn’t afford paying for the travel to the Aegean islands. (…) If you are a Turkish citizen – we have many migrants who are Turkish who have applied for asylum here in Greece – you are automatically accused of being the smuggler or the driver of the boat.”

Rûnbîr Serkepkanî, CPT-Lesvos, March 2019

Dariusz Firla from CPT-Lesvos describes how people labelled as “smugglers” are often identified:

“When the Coast Guard or FRONTEX pick up refugees at sea, they usually ask directly: “Who drove the boat?”. Sometimes people even say, “That was me,” because they don’t know it’s a crime. In some cases, it is simply a matter of refugees who paid less and drive the boat for this, but often it is Turks from poor regions who, for example, had no work and were hired by the smugglers for some pocket money to go and return the boat. Sometimes they are beaten bloody after their arrest until they arrive at the port.”

Dariusz Firla, CPT Lesvos, June 2017

CPT-Lesvos interviewed Tarek (name changed) from Syria who has been detained in Chios prison for 14 months. He explained: “I was beaten from the moment I was arrested at sea until arriving at the police station. I was bleeding.”

After their arrest, people are held in pre-trial detention. CPT-Lesvos found that migrants are on average detained for 7 months before their first trial. There were also cases where the trial was postponed twice, leading to 29 months of pre-detention.

A farce of a court case

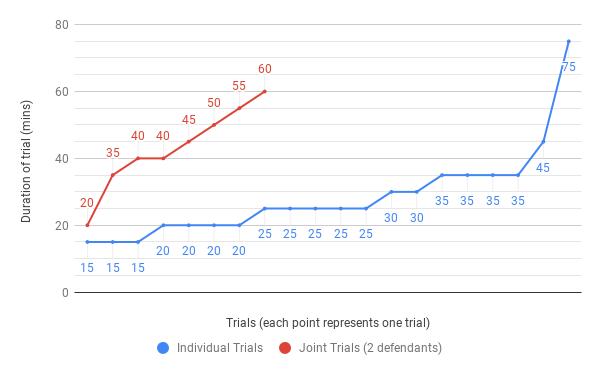

One of the major problems in court is a shocking lack of deep processing. CPT-Lesvos timed the duration of 28 trials and found that the average duration of an individual trial was only 28.5 minutes, while the average duration of a joint trial was 43 minutes. Obviously, this makes a thorough investigation of the question of guilt impossible. Furthermore, the translation within the trials is extremely poor.

In many cases, the defendants are sentenced even if there is hardly any evidence against them. Dariusz Firla explains:

“Sometimes there is only the Coast Guard as witness. For the judges, it can be sufficient if the witness identifies the defendant as the driver of the boat. In one case, the Coast Guard even stated that he had not been present at the rescue operation himself, but that his colleague had told him that the defendant was guilty.”

Dariusz Firla, CPT Lesvos, June 2017

On top of the lack of deep processing by the judges, the quality of the court-appointed lawyers poses a major problem, especially since most lawyers are only appointed at the day of the trial and have no means to do any investigation for the defence. Sometimes, state or private lawyers also do not appear before the court, as in the case of Tarek (name changed), who had spent 14 months in pre-trial detention. Tarek’s family sold whatever they could to pay for a Greek lawyer, but the lawyer failed to show up on the day of the trial and he was sentenced to 45 years in prison.

Life long sentences

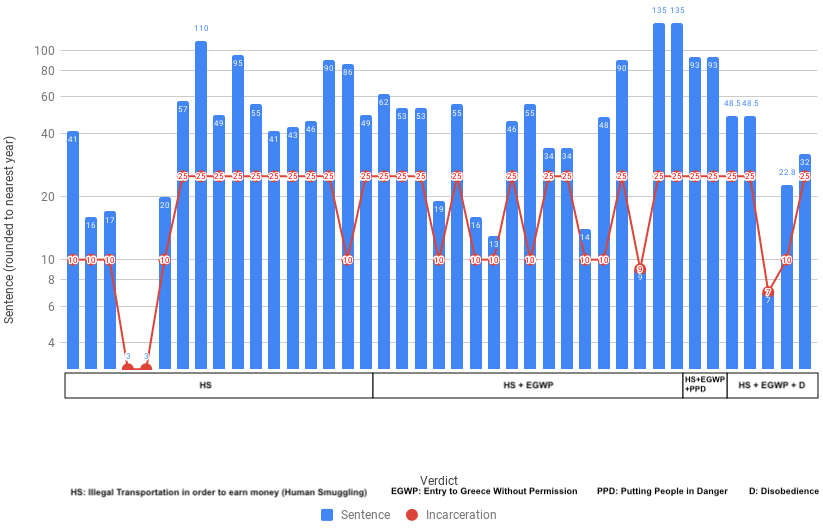

In nearly all cases, the accused migrants are found guilty of human smuggling and in some cases also of entry to Greece without permission and disobedience. Rûnbîr Serkepkanî states:

“The punishment of people who are accused with or charged with smuggling is higher than murder in Greece. So it is more serious to drive a boat which carries migrants to the Greek islands than murdering people.”

Rûnbîr Serkepkanî, CPT-Lesvos, March 2019

The sentences are calculated adding factors such as the number of people transported, transport without life vests, and if their lives were put in danger (e.g. through capsizing of the boat), which is why the sentence can exceed 100 years. Since the maximum period of factual imprisonment in Greece is 25 years, the sentences is then reduced accordingly. In some cases, mitigating circumstances are taken into account, reducing the penalty to about ten years. Sometimes the deportation of the convicted person is ordered directly after the release. In fact, looking at 41 cases between 2016 and 2017, CPT-Lesvos found that the average sentence of the trials they monitored was about 44 years in prison with an expected actual duration in prison of about 19 years. In addition, there are huge fines imposed, on average more than 370.000 Euros.

| Charge | Average Sentence (41 cases) |

Average time the sentence is to be served (41 cases) |

| (1) human smuggling (illegal transportation in order to earn money) | 48 years | 18 years |

| (1) human smuggling (illegal transportation in order to earn money) (2) entry to Greece without permission |

51 years | 19 years |

| (1) human smuggling (illegal transportation in order to earn money) (2) entry to Greece without permission (3) disobedience |

32 years | 19.5 years |

The European incarceration of the marginalized

The necessity to prevent human smuggling has been normalized in the European Union. Arrests are supported by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency FRONTEX and hardly any politician would question the necessity to prevent human smuggling at the EU external borders. The actions of the Greek state and courts are either tacitly supported or ignored.

The EU Commission, FRONTEX and interior ministries tend to mention the need to fight human smuggling in one breath with the necessity to save lives and ensure protection of humans. This was especially made possible through the convergence of discourses around human trafficking, human smuggling and escape aid.[4] The EU claims:

“While trafficking in human beings and migrant smuggling are two different crimes subject to different legal frameworks they are closely interlinked.”

European Union, 15.10.2018[5]

Trafficking and smuggling may overlap in some cases, however, they are in fact two completely different issues. Trafficking is a forced transfer of people, connected to kidnapping, exploitation and modern slavery, while human smuggling is a response on the restrictive border policies preventing even refugees to be able to cross borders in a legal way.

For the majority of the worldwide population, there is no safe passage and no legal way to enter an EU country and seek asylum or receive a working visa. People are forced to embark on illegalized deadly routes and have no other option but to use the service of facilitators that are in many cases excessively overpriced and risky. The facilitation of people’s journeys is illegalized even if their right to stay is approved through an asylum decision afterwards. Destroying smuggling networks will not save lives – people rely on them to save their own lives.

As the example of Greece shows, the people who are arrested in the fight against human smuggling are exactly those already suffering most from the EU border policies. In many cases, they had no choice and are themselves seeking protection. The anti-smuggling policies at the external border of Greece only hit the smallest link in a chain. Since people often have neither information on the risks they undergo nor a choice, these policies do not even have a deterring effect and only follow a senseless ideology of punishment. Without any need, the lives of marginalized people are destroyed in devastating ways. It is migrants and refugees seeking protection – unheard and without any lobby – who have to pay with their lives and dreams for these misguided and inhumane European policies.

[1]European Union (2018): The EU’s global engagement to counter smuggling and trafficking networks, 15.10.2018.

[2] For a recent arrest, see e.g.: Ekathimerini.com, 11.07.2019: Three arrested for migrant smuggling in as many incidents.

[3] See also: CPT Europe, 01.12.2016: Seeing in the Greek Courtroom.

[4] For an in-depth analysis see: Bellezza, Sara; Calandrino, Tiziana, March 2017: Criminalization of Flight and Escape Aid. Borderline-europe.

[5]European Union (2018): The EU’s global engagement to counter smuggling and trafficking networks, 15.10.2018.